Narrative Materiality: The Pilgrimage

El Camino de Santiago, 2017

“Soñar el sueño imposible, luchar contra el enemigo imposible, correr donde valientes no se atrevieron, alcanzar la estrella inalcanzable. Ese es mi destino.” - Don Quijote

Cervantes said it best: “To dream the impossible dream, to fight the impossible enemy to run where the brave did not dare, to reach the unreachable star. That is my destiny.”

This project is beginning to feel much bigger than me. I began with the dream that I would collect these awe-inspiring stories and create an installation so beautiful, so meaningful, that not only would I get an ‘A,’, but I would unearth a common humanity in a time when we feel so very separated.

Then, tonight, I received an email from Betty, a stranger who responded to my NextDoor post asking for pilgrims to share their stories with me. Betty is not a typical pilgrim and, as an older adult, she was unsure of how to record or send me her story. Luckily, after much back and forth about possible options, her son (a “techie”) was due for a visit and was able to record her and email me her audio.

Betty revealed that she and her husband Larry, at the ages of 65 and 71, decided to complete their bucket lists: to move to a foreign country, and, for her husband, to walk the 550 miles of El Camino de Santiago. The pair rented an apartment in Spain in preparation. Larry walked and trained for months in Costa Rica before getting sick with what they thought was the flu. He died in Austin, Texas, from what turned out to be advanced Leukemia. Afterwards, Betty flew with her sister to and spread Larry’s ashes in the Atlantic Ocean. She described the ashes in the wind as a “black ribbon” and spoke to how respectful the other pilgrims and tourists were of this moment.

I’m ashamed to admit that Betty’s email not only made me cry like a baby, but also struck a selfish fear in my heart: how can I possibly represent this woman’s incredible story in a meaningful way? My small installation, with all of the limitations of COVID-19, budget, technical proficiency, and overall capability seem to fall short of such an important story.

Process Notes

Step One: gathering stories and source material

Methods:

Reaching out to people I know personally via email, WhatsApp, Instagram, and email

Putting out a call for participants via Instagram and NextDoor

Challenges:

Finding male voices! So far, I’ve only been able to find female perspectives

Because a pilgrimage is, by nature, such a personal experience, some people are uncomfortable sharing their experiences either because they do not know how to express their experience or, more importantly, they find it dilutes their personal experience

So far:

Sydney - El Camino de Santiago

Ruth - The Colorado Trail

Melina - Jewish Birthright to Israel

Eli? - Jewish Birthright to Israel

Ayesha?

Alexandra? - grandmother’s pilgrimage to America

Karla (NextDoor) - ?

Karla’s friend who leads pilgrimages?

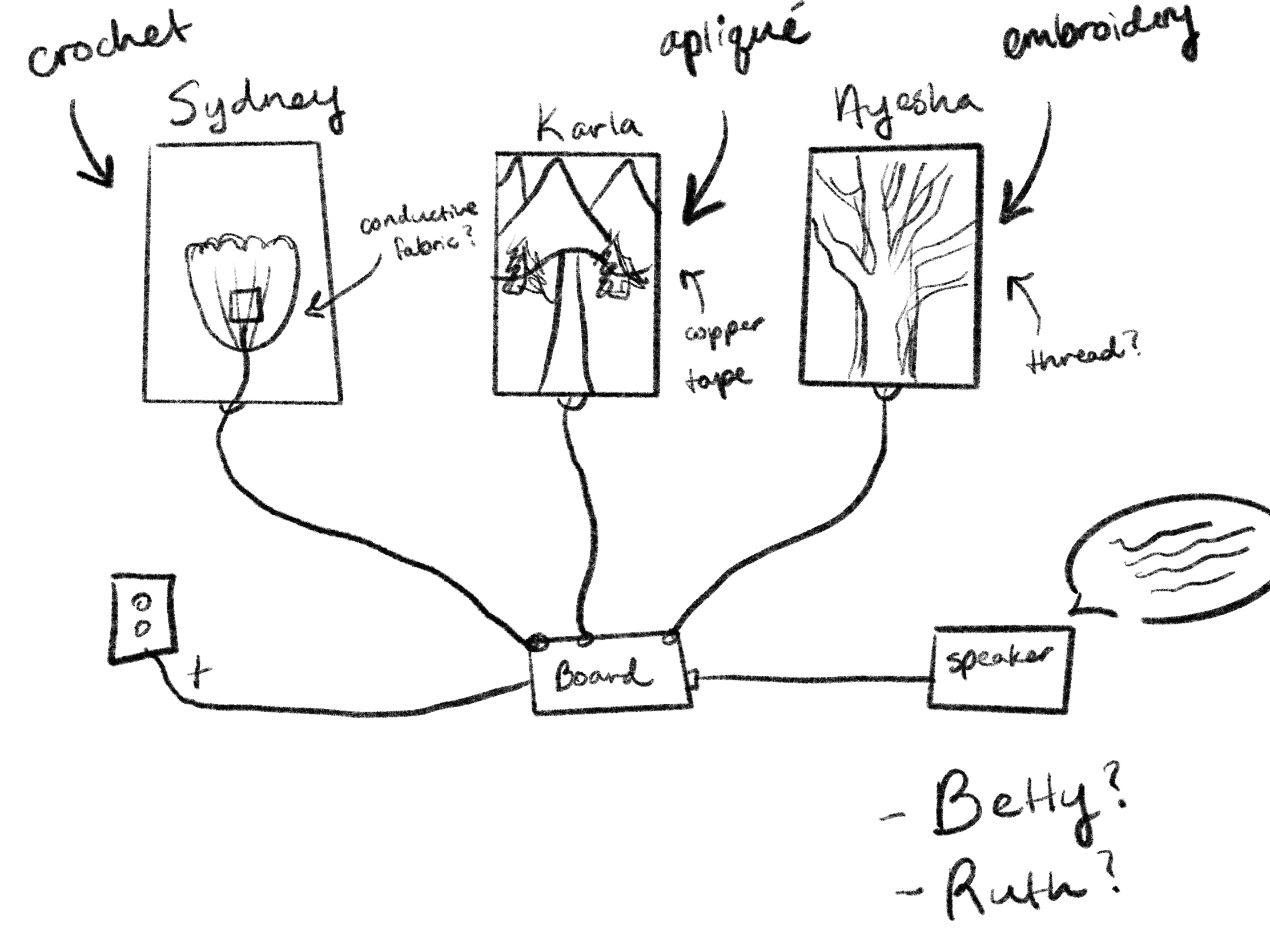

Basic Schematic

Concept: Audio-Visual Pilgrimage with Waypoints Created with Textile Manipulation

Inspired by Angie Eng’s “This Land is My Land,” this audio-visual installation will use various forms of textile manipulation — crochet, embroidery, sewing, etc. — to depict images representative of pilgrimages, and crafted with conductive thread which will trigger a spoken narrative of a pilgrim’s story when interacted with by the user.

Materials Needed:

conductive thread

headphones?

method of transmitting audio

yarn

fabric

thread

frames

stories from different pilgrimages

Narrative: The Pilgrimage

As detailed below, I have a long history of witnessing and semi-participating in pilgrimages, but never fully committing to one. I consider a pilgrimage not just in the religious sense. A pilgrimage could certainly be to a holy site, and this is often what we associate them with. However, a pilgrimage could also be committing to hiking The Colorado Trail. The significance of a pilgrimage may come from the destination, to be sure, but the reason people embark on a journey from Point A to Point B is in the seeking of a transformation of some kind. Religious, spiritual, self-actualizing, self-improvement, adventure…as J.R.R. Tolkien famously said, “Not all who wander are lost.”

The pilgrimage is perhaps a most literal narrative form. As someone else said, “in all stories, either someone leaves home or someone new comes to town.” What I love about this particular narrative, however, is that each and every pilgrim gets to be the hero in their own story. A pilgrimage is a quest. Whatever personal motivations may have spurred that quest, the communal aspect of walking along a more popular route such as the road to Chimayo or El Camino de Santiago reduces each person’s immediate goal to taking that next step. Along the way, whether the pilgrim bonds with others or keeping to themself, each of those steps amounts to something much more profound: a metamorphic, liminal time and space in which people both lose and find themselves.

Background: The Personal History of A Pilgrimage “Bystander”

El Santuario de Chimayo

Strangely, or perhaps significantly, for much of my life I have lived very near famous pilgrimage routes. Yet, I myself have never embarked upon a full pilgrimage.

I grew up in the Southwest corner of Colorado, close enough to make at least an annual drive to El Santuario de Chimayo, a humble adobe church nestled within the Sangre de Cristo mountain range and constructed by the Spaniards in the early 1800s. Every year, over three hundred thousand pilgrims, primarily Native Americans and Latinx/Chicanx Catholics, but representing all corners of the globe, trek over one hundred miles from various directions to the tiny village of Chimayo, New Mexico, in the largest pilgrimage in North America. More specifically, they travel to El Pocito (the Little Well), a tiny candlelit room to the side of the main altar with a ceiling so low-flung that most who enter are forced to stoop. A small earthen hole, about three feet in circumference and one to two feet in depth, is carved within the rough stone floor, and filled with earth that people collect in small jars. While this seems like a rather anticlimactic end to a trek that many make barefoot or even hauling huge, wooden crosses, this “mundane dirt” is actually none other than the legendary tierra bendita, “Sacred Earth,” believed to possess extraordinary healing powers.

The deeply spiritual significance afforded to this healing earth, as well as the transformative, symbolic meaning of the act of pilgrimage to the site, results from the cultural hybridity of two distinct societies in northern New Mexico: that of the indigenous Tewa-speaking Pueblo Indians, and that of the Spanish Hermanos Penitente, “Penitente Brotherhood.” The earth was originally a symbolic site for the Ancient Pueblo Indigenous of approximately A.D. 110 and A.D. 1400, who understood the site as one of the focal points that demarcated their sacral topography. According to Pueblo mythology, the natural world is marked with powerful points of entry into other cosmic levels, with the earthen hole at Chimayo (Tsimajo’onwi in Tewa) serving as a node of entry into the underworld, from which humans first came and to which they must return with death. When the Penitente Brotherhood emerged in northern New Mexico in the late eighteenth century, they sought to fuse indigenous religious practices with those of the Catholic Church. In the typical imperialistic manner, the Spaniards built a church over Tsimajo’onwi, claiming the site as one of Catholic mythological significance in the process (in the revised story, a priest noticed a bright light shining from beneath the earth, dug into the ground, and found a crucifix, then built El Santuario).

While my abuela insisted that we go to Chimayo at least once a year to refill her little jar of sacred dirt — which was liable to be rubbed on your forehead whenever you were sick or injured — we never participated in the pilgrimage. We certainly witnessed the pilgrims, especially during Holy Week. Many were atoning for something or injured in some way, limping along and stooped with guilt, a bad back, or both. Some hobbled on crutches, some traveled in wheelchairs, and many walked barefoot or crawled along the ground in penitence. Some carried huge wooden crosses. As a child, I remember being slightly frightened by the sweaty, dusty travelers (especially since I was unfairly forced to wear formal clothes for mass). The mystery and importance surrounding the whole event, however, intrigued me. I could tell this community of pilgrims was participating in something ritualistic and profound, something beyond a little jar of dirt.

In Spain, our apartment was literally above the infamous El Camino de Santiago — with our entrance door bearing one of the ancient seashells that marks the trail. Most days, we looked down from our balcony on groups of peregrinos, “pilgrims,” from all across the globe. We wondered at the individuals who wandered below us, playing drinking games to see who could compose the most compelling narrative. Some were simply adventure enthusiasts, looking to tick an item off of their travel bucket list. Some were the outdoorsy type, seeking to prove their physical capability and stamina. Some had much deeper motivations. People who had lost someone, either romantically or through death, looking to heal and fall back in love with themselves and life. Twenty-something year olds, searching for self-actualization and to untangle the chaotic future that lay before them. Seventy-something year olds, reflecting on the people and circumstances that had gotten them this far. Some (myself included) only walked sections of El Camino. Some traveled the entire 500 miles from Southern France to the other side of the country.

Living where we did, in Logroño, La Rioja, a central waypoint on the trek, El Camino was a part of our daily lives. As some of the only Americans and English speakers in our small city, we were frequent travel advisors to pilgrims we’d meet as we downed espresso in the cafe below our apartment before work. As a teacher, our classes took field trips to hike sections of El Camino to the next town (I’m still amazed at the hardiness expected of third graders in Spain — I’m fairly certain that forcing eight year olds to walk over ten miles would be illegal in the U.S.). The infamous trail markers — scallop shells to signify both religious attributes of Saint James as well as the visual signifier of many paths leading to the same point — were embedded in the walls and the streets of the city and dangled from the backpacks of the pilgrims. Yet, while we literally lived on the trail, we never committed to the month-plus required to walk the entire Camino.